13/01/26

Being text of lecture delivered at 2026 Annual Convention of 1992 Set, PCC Ihioma

By Livy-Elcon Emereonye

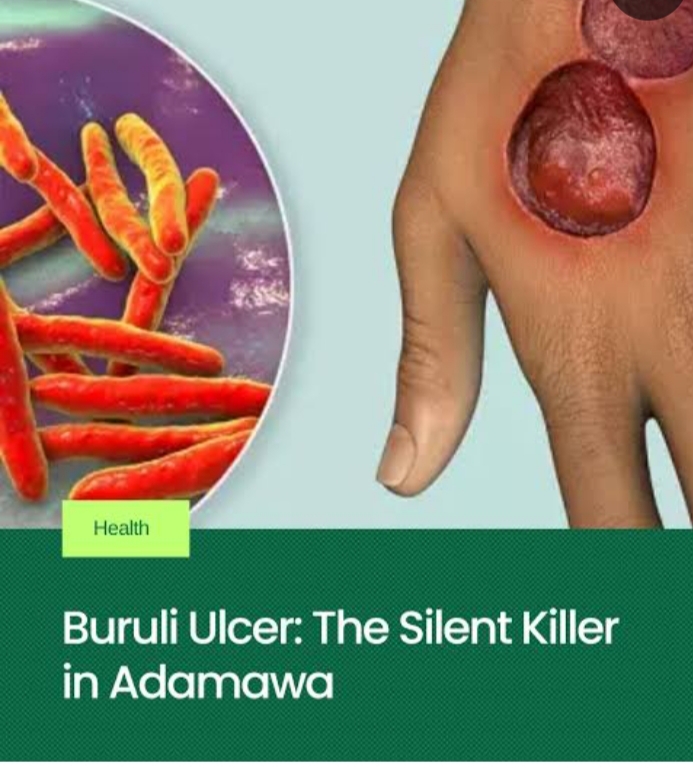

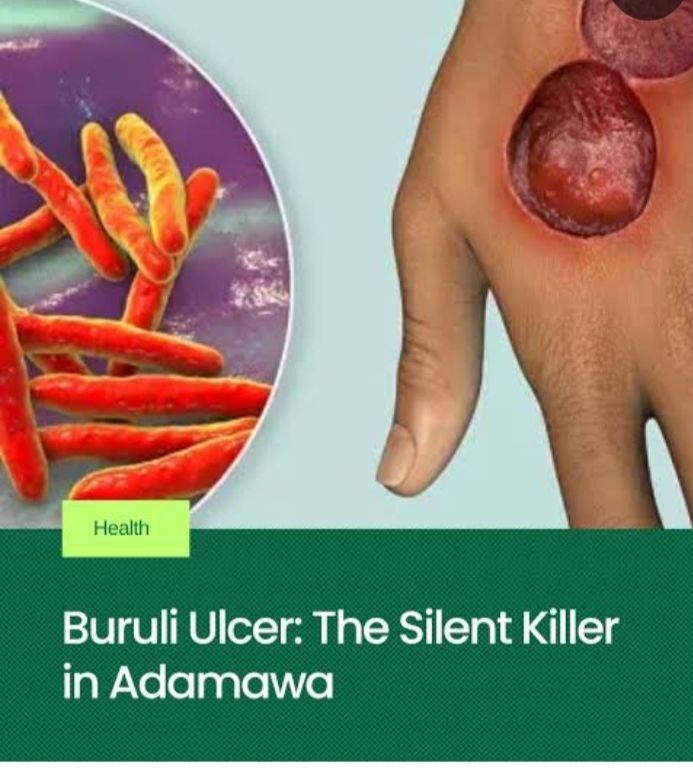

Buruli ulcer (BU), locally referred to in parts of Igboland as Achaere, is a neglected tropical disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans. Despite effective antibiotic regimens recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), delayed presentation, sociocultural interpretations, and inappropriate traditional interventions continue to fuel high morbidity, deformity, and disability in endemic regions.

An Integrative Medicine Approach to the Management of Achaere (Buruli Ulcer)

- Introduction

Among the most severe but least addressed neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) is Buruli ulcer. Ranked after tuberculosis and leprosy among mycobacterial infections, BU disproportionately affects rural populations in West and Central Africa, including Nigeria, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Cameroon. In endemic Nigerian communities, particularly among the Igbo, the disease is colloquially known as Achaere, a term that often carries cultural, spiritual, or metaphysical interpretations.

These interpretations, though culturally meaningful, frequently delay biomedical intervention. Patients often present late, with advanced ulcers, secondary infection, bone involvement, and irreversible disability. At the same time, African traditional medicine remains the first line of care for many rural populations due to accessibility, affordability, and cultural trust.

This reality necessitates not a dismissal of traditional medicine, but a critical scientific engagement with it. The goal of this review is to examine medicinal plants traditionally used for Achaere, evaluate their evidence base, and propose a rational integrative framework that aligns ethnomedical knowledge with modern infectious disease management.

- Epidemiology and Public Health Significance

Buruli ulcer is endemic in over 33 countries worldwide, with Africa accounting for the vast majority of cases. Children under 15 years constitute a significant proportion of patients, although adults are also affected. The disease is closely associated with riverine and swampy environments, agricultural activity, and limited access to healthcare.

In Nigeria, underreporting remains a major challenge. Many cases never reach hospitals, instead being managed in traditional settings until complications arise. This contributes to the perception that BU is incurable or spiritually driven, further entrenching harmful treatment practices.

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

3.1 Causative Agent

Buruli ulcer is caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans, an environmental mycobacterium distinct from M. tuberculosis and M. leprae. Its unique pathogenicity lies in its production of mycolactone, a lipid toxin.

Mycobacterium ulcerans are rod-shaped, Gram positive bacteria that grow slowly, forming small transparent colonies after four weeks when viewed on a microscope.

Mosquitoes and other aquatic insects (like water bugs) are the primary vectors transmitting the ulcer-causing bacteria Mycobacterium ulcerans from the environment to people.

3.2 Role of Mycolactone

Mycolactone is a nasty toxin:

- Induces apoptosis of skin and subcutaneous cells leading to ulcers and tissue damage.

- Suppresses local immune responses

- Explains the painless nature of early lesions

As a result, patients often ignore early nodules or plaques until extensive tissue destruction has occurred.

3.3 The Role of Immunity

In Buruli ulcer, immunity plays a crucial role:

- The disease often affects people with weakened immune systems.

- Research suggests that a strong cell-mediated immune response is key to controlling M. ulcerans infection.

- Mycolactone suppresses the immune system, making it harder for the body to fight the infection.

Early treatment and a healthy immune system can improve outcomes.

- Clinical Presentation

4.1 Early Lesions

- Painless nodules

- Firm plaques

- Diffuse, non-pitting edema

4.2 Advanced Disease

- Large ulcers with undermined edges

- Necrosis of skin and subcutaneous tissue

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Osteomyelitis

- Deformity and contractures

Pain typically appears late, often signaling secondary infection rather than primary disease activity.

- Conventional Management of Buruli Ulcer

Diagnosis

- Clinical examination (in endemic areas)

- Laboratory confirmation:

-PCR testing (gold standard)

-Microscopy

-Culture (slow) - Histopathology in some cases

Treatment of Achaere (Buruli Ulcer)

Conventional Treatment

WHO-recommended treatment consists of 8 weeks of combination antibiotic therapy, usually:

- Rifampicin + Clarithromycin

This regimen achieves cure rates exceeding 90% when initiated early.

- (or Rifampicin + Streptomycin in some settings)

Wound Care

- Regular sterile dressing

- Debridement of dead tissue

- Skin grafting in advanced cases

- Physiotherapy to prevent deformities

- Psychosocial support.

Surgery

- Reserved for large or complicated ulcers

- Used alongside antibiotics, not alone

- The Place of Traditional Medicine in Achaere

In many African communities, traditional medicine is not an alternative but the default healthcare system. However, in the context of Buruli ulcer, certain practices—scarification, caustic herbal pastes, hot compresses—have been shown to worsen tissue necrosis and delay healing.

The challenge, therefore, is to separate empirically harmful practices from potentially beneficial plant-based interventions, and to reframe traditional medicine as a supportive, regulated, and evidence-informed partner.

- Medicinal Plants Used in the Supportive Management of Achaere

7.1 Azadirachta indica (Neem)

Neem is one of the most widely studied medicinal plants in tropical medicine. Its bioactive compounds—nimbidin, azadirachtin, quercetin—exhibit antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties.

Relevance to Achaere:

Neem shows inhibitory effects against Mycobacterium species and common wound pathogens. Mild decoctions may be used for wound cleansing, provided they are non-caustic and sterile.

7.2 Vernonia amygdalina (Bitter Leaf)

A cornerstone of Igbo ethnomedicine, V. amygdalina contains sesquiterpene lactones and flavonoids with antimicrobial and antioxidant effects.

It is used primarily as oral immune support and metabolic modulation rather than direct ulcer application.

7.3 Psidium guajava (Guava Leaves)

Guava leaves possess strong antibacterial and astringent properties, effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—key secondary invaders in chronic ulcers.

It has adjunct role in wound cleansing and exudate control.

7.4 Carica papaya (Pawpaw)

Papaya latex contains papain, a proteolytic enzyme used in enzymatic debridement.

It should be noted that while beneficial when standardized, crude latex may cause irritation and should not be applied indiscriminately.

7.5 Aloe vera

Aloe vera promotes epithelialization, reduces inflammation, and minimizes scar formation.

It is best suited for healing stages rather than active necrotic ulcers.

7.6 Curcuma longa (Turmeric)

Curcumin exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-modulatory properties.

Its application should be for oral supplementation; and raw powder should not be packed into ulcers.

7.7 Ocimum gratissimum (Nchuanwu / Scent Leaf)

Contains eugenol and thymol with antimicrobial activity.

It can be used for mild topical cleansing and general skin hygiene.

7.8 Medical-Grade Honey

Unlike raw honey, medical-grade honey is sterilized and standardized.

It has demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and accelerates wound healing.

- Safety, Ethics, and Cultural Responsibility

The integration of medicinal plants into Buruli ulcer management must adhere to:

- Non-maleficence

- Standardization

- Supervision

- Clear communication that herbs are adjunctive

Ethically, healthcare providers must respect cultural beliefs while firmly discouraging harmful practices.

- Proposed Integrative Model for Achaere Management

- Early diagnosis and antibiotic therapy

- Professional wound care

- Selected herbal adjuncts with known safety profiles

- Nutritional rehabilitation

- Community education and surveillance

This model aligns biomedical efficacy with cultural relevance.

- Future Research Directions

- Phytochemical isolation of anti-mycolactone compounds

- Toxicity profiling of commonly used herbs

- Controlled clinical trials of adjunctive herbal therapies

- Development of standardized African herbaceutical wound products

- Conclusion

Achaere (Buruli ulcer) is neither mystical nor incurable. It is a bacterial disease whose devastation is amplified by delayed care and harmful interventions. African medicinal plants, when subjected to scientific scrutiny and ethical integration, hold value as supportive tools in comprehensive care. The future of Buruli ulcer management in Africa lies not in rejecting tradition, but in disciplining it with science.

Above all, every problem has a solution even at infinity.

Thanks and God bless.

Being text of lecture delivered at 2026 Annual Convention of 1992 Set, PCC Ihioma

By Livy-Elcon Emereonye

Buruli ulcer (BU), locally referred to in parts of Igboland as Achaere, is a neglected tropical disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans. Despite effective antibiotic regimens recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), delayed presentation, sociocultural interpretations, and inappropriate traditional interventions continue to fuel high morbidity, deformity, and disability in endemic regions.

- Introduction

Among the most severe but least addressed neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) is Buruli ulcer. Ranked after tuberculosis and leprosy among mycobacterial infections, BU disproportionately affects rural populations in West and Central Africa, including Nigeria, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Cameroon. In endemic Nigerian communities, particularly among the Igbo, the disease is colloquially known as Achaere, a term that often carries cultural, spiritual, or metaphysical interpretations.

These interpretations, though culturally meaningful, frequently delay biomedical intervention. Patients often present late, with advanced ulcers, secondary infection, bone involvement, and irreversible disability. At the same time, African traditional medicine remains the first line of care for many rural populations due to accessibility, affordability, and cultural trust.

This reality necessitates not a dismissal of traditional medicine, but a critical scientific engagement with it. The goal of this review is to examine medicinal plants traditionally used for Achaere, evaluate their evidence base, and propose a rational integrative framework that aligns ethnomedical knowledge with modern infectious disease management.

- Epidemiology and Public Health Significance

Buruli ulcer is endemic in over 33 countries worldwide, with Africa accounting for the vast majority of cases. Children under 15 years constitute a significant proportion of patients, although adults are also affected. The disease is closely associated with riverine and swampy environments, agricultural activity, and limited access to healthcare.

In Nigeria, underreporting remains a major challenge. Many cases never reach hospitals, instead being managed in traditional settings until complications arise. This contributes to the perception that BU is incurable or spiritually driven, further entrenching harmful treatment practices.

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

3.1 Causative Agent

Buruli ulcer is caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans, an environmental mycobacterium distinct from M. tuberculosis and M. leprae. Its unique pathogenicity lies in its production of mycolactone, a lipid toxin.

Mycobacterium ulcerans are rod-shaped, Gram positive bacteria that grow slowly, forming small transparent colonies after four weeks when viewed on a microscope.

Mosquitoes and other aquatic insects (like water bugs) are the primary vectors transmitting the ulcer-causing bacteria Mycobacterium ulcerans from the environment to people.

3.2 Role of Mycolactone

Mycolactone is a nasty toxin:

- Induces apoptosis of skin and subcutaneous cells leading to ulcers and tissue damage.

- Suppresses local immune responses

- Explains the painless nature of early lesions

As a result, patients often ignore early nodules or plaques until extensive tissue destruction has occurred.

3.3 The Role of Immunity

In Buruli ulcer, immunity plays a crucial role:

- The disease often affects people with weakened immune systems.

- Research suggests that a strong cell-mediated immune response is key to controlling M. ulcerans infection.

- Mycolactone suppresses the immune system, making it harder for the body to fight the infection.

Early treatment and a healthy immune system can improve outcomes.

- Clinical Presentation

4.1 Early Lesions

- Painless nodules

- Firm plaques

- Diffuse, non-pitting edema

4.2 Advanced Disease

- Large ulcers with undermined edges

- Necrosis of skin and subcutaneous tissue

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Osteomyelitis

- Deformity and contractures

Pain typically appears late, often signaling secondary infection rather than primary disease activity.

- Conventional Management of Buruli Ulcer

Diagnosis

- Clinical examination (in endemic areas)

- Laboratory confirmation:

-PCR testing (gold standard)

-Microscopy

-Culture (slow) - Histopathology in some cases

Treatment of Achaere (Buruli Ulcer)

Conventional Treatment

WHO-recommended treatment consists of 8 weeks of combination antibiotic therapy, usually:

- Rifampicin + Clarithromycin

This regimen achieves cure rates exceeding 90% when initiated early.

- (or Rifampicin + Streptomycin in some settings)

Wound Care

- Regular sterile dressing

- Debridement of dead tissue

- Skin grafting in advanced cases

- Physiotherapy to prevent deformities

- Psychosocial support.

Surgery

- Reserved for large or complicated ulcers

- Used alongside antibiotics, not alone

- The Place of Traditional Medicine in Achaere

In many African communities, traditional medicine is not an alternative but the default healthcare system. However, in the context of Buruli ulcer, certain practices—scarification, caustic herbal pastes, hot compresses—have been shown to worsen tissue necrosis and delay healing.

The challenge, therefore, is to separate empirically harmful practices from potentially beneficial plant-based interventions, and to reframe traditional medicine as a supportive, regulated, and evidence-informed partner.

- Medicinal Plants Used in the Supportive Management of Achaere

7.1 Azadirachta indica (Neem)

Neem is one of the most widely studied medicinal plants in tropical medicine. Its bioactive compounds—nimbidin, azadirachtin, quercetin—exhibit antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties.

Relevance to Achaere:

Neem shows inhibitory effects against Mycobacterium species and common wound pathogens. Mild decoctions may be used for wound cleansing, provided they are non-caustic and sterile.

7.2 Vernonia amygdalina (Bitter Leaf)

A cornerstone of Igbo ethnomedicine, V. amygdalina contains sesquiterpene lactones and flavonoids with antimicrobial and antioxidant effects.

It is used primarily as oral immune support and metabolic modulation rather than direct ulcer application.

7.3 Psidium guajava (Guava Leaves)

Guava leaves possess strong antibacterial and astringent properties, effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—key secondary invaders in chronic ulcers.

It has adjunct role in wound cleansing and exudate control.

7.4 Carica papaya (Pawpaw)

Papaya latex contains papain, a proteolytic enzyme used in enzymatic debridement.

It should be noted that while beneficial when standardized, crude latex may cause irritation and should not be applied indiscriminately.

7.5 Aloe vera

Aloe vera promotes epithelialization, reduces inflammation, and minimizes scar formation.

It is best suited for healing stages rather than active necrotic ulcers.

7.6 Curcuma longa (Turmeric)

Curcumin exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-modulatory properties.

Its application should be for oral supplementation; and raw powder should not be packed into ulcers.

7.7 Ocimum gratissimum (Nchuanwu / Scent Leaf)

Contains eugenol and thymol with antimicrobial activity.

It can be used for mild topical cleansing and general skin hygiene.

7.8 Medical-Grade Honey

Unlike raw honey, medical-grade honey is sterilized and standardized.

It has demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and accelerates wound healing.

- Safety, Ethics, and Cultural Responsibility

The integration of medicinal plants into Buruli ulcer management must adhere to:

- Non-maleficence

- Standardization

- Supervision

- Clear communication that herbs are adjunctive

Ethically, healthcare providers must respect cultural beliefs while firmly discouraging harmful practices.

- Proposed Integrative Model for Achaere Management

- Early diagnosis and antibiotic therapy

- Professional wound care

- Selected herbal adjuncts with known safety profiles

- Nutritional rehabilitation

- Community education and surveillance

This model aligns biomedical efficacy with cultural relevance.

- Future Research Directions

- Phytochemical isolation of anti-mycolactone compounds

- Toxicity profiling of commonly used herbs

- Controlled clinical trials of adjunctive herbal therapies

- Development of standardized African herbaceutical wound products

- Conclusion

Achaere (Buruli ulcer) is neither mystical nor incurable. It is a bacterial disease whose devastation is amplified by delayed care and harmful interventions. African medicinal plants, when subjected to scientific scrutiny and ethical integration, hold value as supportive tools in comprehensive care. The future of Buruli ulcer management in Africa lies not in rejecting tradition, but in disciplining it with science.

Above all, every problem has a solution even at infinity.

Thanks and God bless.

An Integrative Medicine Approach to the Management of Achaere (Buruli Ulcer)

Being text of lecture delivered at 2026 Annual Convention of 1992 Set, PCC Ihioma

By Livy-Elcon Emereonye

Buruli ulcer (BU), locally referred to in parts of Igboland as Achaere, is a neglected tropical disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans. Despite effective antibiotic regimens recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), delayed presentation, sociocultural interpretations, and inappropriate traditional interventions continue to fuel high morbidity, deformity, and disability in endemic regions.

- Introduction

Among the most severe but least addressed neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) is Buruli ulcer. Ranked after tuberculosis and leprosy among mycobacterial infections, BU disproportionately affects rural populations in West and Central Africa, including Nigeria, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Cameroon. In endemic Nigerian communities, particularly among the Igbo, the disease is colloquially known as Achaere, a term that often carries cultural, spiritual, or metaphysical interpretations.

These interpretations, though culturally meaningful, frequently delay biomedical intervention. Patients often present late, with advanced ulcers, secondary infection, bone involvement, and irreversible disability. At the same time, African traditional medicine remains the first line of care for many rural populations due to accessibility, affordability, and cultural trust.

This reality necessitates not a dismissal of traditional medicine, but a critical scientific engagement with it. The goal of this review is to examine medicinal plants traditionally used for Achaere, evaluate their evidence base, and propose a rational integrative framework that aligns ethnomedical knowledge with modern infectious disease management.

- Epidemiology and Public Health Significance

Buruli ulcer is endemic in over 33 countries worldwide, with Africa accounting for the vast majority of cases. Children under 15 years constitute a significant proportion of patients, although adults are also affected. The disease is closely associated with riverine and swampy environments, agricultural activity, and limited access to healthcare.

In Nigeria, underreporting remains a major challenge. Many cases never reach hospitals, instead being managed in traditional settings until complications arise. This contributes to the perception that BU is incurable or spiritually driven, further entrenching harmful treatment practices.

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

3.1 Causative Agent

Buruli ulcer is caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans, an environmental mycobacterium distinct from M. tuberculosis and M. leprae. Its unique pathogenicity lies in its production of mycolactone, a lipid toxin.

Mycobacterium ulcerans are rod-shaped, Gram positive bacteria that grow slowly, forming small transparent colonies after four weeks when viewed on a microscope.

Mosquitoes and other aquatic insects (like water bugs) are the primary vectors transmitting the ulcer-causing bacteria Mycobacterium ulcerans from the environment to people.

3.2 Role of Mycolactone

Mycolactone is a nasty toxin:

- Induces apoptosis of skin and subcutaneous cells leading to ulcers and tissue damage.

- Suppresses local immune responses

- Explains the painless nature of early lesions

As a result, patients often ignore early nodules or plaques until extensive tissue destruction has occurred.

3.3 The Role of Immunity

In Buruli ulcer, immunity plays a crucial role:

- The disease often affects people with weakened immune systems.

- Research suggests that a strong cell-mediated immune response is key to controlling M. ulcerans infection.

- Mycolactone suppresses the immune system, making it harder for the body to fight the infection.

Early treatment and a healthy immune system can improve outcomes.

- Clinical Presentation

4.1 Early Lesions

- Painless nodules

- Firm plaques

- Diffuse, non-pitting edema

4.2 Advanced Disease

- Large ulcers with undermined edges

- Necrosis of skin and subcutaneous tissue

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Osteomyelitis

- Deformity and contractures

Pain typically appears late, often signaling secondary infection rather than primary disease activity.

- Conventional Management of Buruli Ulcer

Diagnosis

- Clinical examination (in endemic areas)

- Laboratory confirmation:

-PCR testing (gold standard)

-Microscopy

-Culture (slow) - Histopathology in some cases

Treatment of Achaere (Buruli Ulcer)

Conventional Treatment

WHO-recommended treatment consists of 8 weeks of combination antibiotic therapy, usually:

- Rifampicin + Clarithromycin

This regimen achieves cure rates exceeding 90% when initiated early.

- (or Rifampicin + Streptomycin in some settings)

Wound Care

- Regular sterile dressing

- Debridement of dead tissue

- Skin grafting in advanced cases

- Physiotherapy to prevent deformities

- Psychosocial support.

Surgery

- Reserved for large or complicated ulcers

- Used alongside antibiotics, not alone

- The Place of Traditional Medicine in Achaere

In many African communities, traditional medicine is not an alternative but the default healthcare system. However, in the context of Buruli ulcer, certain practices—scarification, caustic herbal pastes, hot compresses—have been shown to worsen tissue necrosis and delay healing.

The challenge, therefore, is to separate empirically harmful practices from potentially beneficial plant-based interventions, and to reframe traditional medicine as a supportive, regulated, and evidence-informed partner.

- Medicinal Plants Used in the Supportive Management of Achaere

7.1 Azadirachta indica (Neem)

Neem is one of the most widely studied medicinal plants in tropical medicine. Its bioactive compounds—nimbidin, azadirachtin, quercetin—exhibit antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties.

Relevance to Achaere:

Neem shows inhibitory effects against Mycobacterium species and common wound pathogens. Mild decoctions may be used for wound cleansing, provided they are non-caustic and sterile.

7.2 Vernonia amygdalina (Bitter Leaf)

A cornerstone of Igbo ethnomedicine, V. amygdalina contains sesquiterpene lactones and flavonoids with antimicrobial and antioxidant effects.

It is used primarily as oral immune support and metabolic modulation rather than direct ulcer application.

7.3 Psidium guajava (Guava Leaves)

Guava leaves possess strong antibacterial and astringent properties, effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—key secondary invaders in chronic ulcers.

It has adjunct role in wound cleansing and exudate control.

7.4 Carica papaya (Pawpaw)

Papaya latex contains papain, a proteolytic enzyme used in enzymatic debridement.

It should be noted that while beneficial when standardized, crude latex may cause irritation and should not be applied indiscriminately.

7.5 Aloe vera

Aloe vera promotes epithelialization, reduces inflammation, and minimizes scar formation.

It is best suited for healing stages rather than active necrotic ulcers.

7.6 Curcuma longa (Turmeric)

Curcumin exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-modulatory properties.

Its application should be for oral supplementation; and raw powder should not be packed into ulcers.

7.7 Ocimum gratissimum (Nchuanwu / Scent Leaf)

Contains eugenol and thymol with antimicrobial activity.

It can be used for mild topical cleansing and general skin hygiene.

7.8 Medical-Grade Honey

Unlike raw honey, medical-grade honey is sterilized and standardized.

It has demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and accelerates wound healing.

- Safety, Ethics, and Cultural Responsibility

The integration of medicinal plants into Buruli ulcer management must adhere to:

- Non-maleficence

- Standardization

- Supervision

- Clear communication that herbs are adjunctive

Ethically, healthcare providers must respect cultural beliefs while firmly discouraging harmful practices.

- Proposed Integrative Model for Achaere Management

- Early diagnosis and antibiotic therapy

- Professional wound care

- Selected herbal adjuncts with known safety profiles

- Nutritional rehabilitation

- Community education and surveillance

This model aligns biomedical efficacy with cultural relevance.

- Future Research Directions

- Phytochemical isolation of anti-mycolactone compounds

- Toxicity profiling of commonly used herbs

- Controlled clinical trials of adjunctive herbal therapies

- Development of standardized African herbaceutical wound products

- Conclusion

Achaere (Buruli ulcer) is neither mystical nor incurable. It is a bacterial disease whose devastation is amplified by delayed care and harmful interventions. African medicinal plants, when subjected to scientific scrutiny and ethical integration, hold value as supportive tools in comprehensive care. The future of Buruli ulcer management in Africa lies not in rejecting tradition, but in disciplining it with science.

Above all, every problem has a solution even at infinity.

Thanks and God bless.